A time-lapse interval, in relation to the speed of the action in front of you, essentially determines the speed of your output video. While these guidelines will help you set a proper time-lapse interval framework, no two scenes or events are exactly alike. It still pays to do a little “back of the photography journal” calculations. This post will help you sort things out.

How to Choose a Time-lapse Interval

I queued up the time-lapse exposure video to the beginning interval section.

(***amature tutorial warning*** 🙂 These were the first I’d ever made, updated videos in the works)

Here are a few things to think about:

What do you want to capture and how long is the event?

What specific event do you want to capture? Is it a full sunrise, a start to finish construction project, or a clip of cars at night on a busy highway, etc. What event and how much of the event you want to capture is the first consideration in determining your interval. [aside]This post on Choosing a timelapse interval is part of a larger road-map outlining timelapse photography called The Massive Time-lapse Photography How to Guide…[/aside]

Determine: How long you need to be present and snapping to record what it is that you want to include in your time-lapse compilation.

How fast is the action taking place?

Think about how fast the scene is changing. Also think about how you would like that change to be displayed in the final time-lapse compilation. For example if you have a fast changing scene and you want to record smooth fluid motion then you will want to set a shorter interval. A slower changing scene can allow a longer interval to still achieve smooth playback. If you want “jerky” motion, where it looks like things pop from one location to another (instead of blending) use a longer interval in a fast scene.

Decide: How you would like the final compilation to flow.

Observe: How fast the scene before you is changing.

The exposure and time-lapse interval tutorial video above shows a side by side comparison of a short and long interval and the resulting speed change.

To give you a feel on where to start here are some common scenes with possible intervals:

1 second

Moving traffic

Fast moving clouds

Drivelapses

1- 3 seconds

Sunsets

Sunrises

Slower moving clouds

Crowds

Moon and sun near horizon (or telephoto)

Things photographed with a telephoto[/one_fourth]

15 – 30 seconds

Moving shadows

Sun across sky (no clouds) (wide)

Stars (15 – 60 seconds)

Longer

Fast growing plants (ex vines) (90 – 120 seconds)

Construction projects (5min – 15min)[/one_fourth_last]

How long do you want your time-lapse compilation to be, and how long to shoot?

Think about how many pictures are required to give you the compilation scene length that you want? Too short and you won’t have enough frames to make a meaningful compilation. (ever see a 4 second time-lapse, by the time you realize what you are watching, it’s over). Too long and you will have unneeded extra frames to transfer and process (not a huge deal though unless you are short on card or hard-drive space).

Sometimes you may need a specific length compilation to fit an assignment or a storyboard segment in a larger time-lapse work. Whatever the case it’s good to do some back of the photography journal calculations. There is one stipulation you need to follow as you do your calculation:

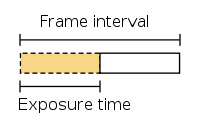

Interval must be longer than exposure

Frame interval > Exposure time

Your interval MUST exceed your exposure time. A good rule of thumb is to keep your exposure at about 60% – 80% of your interval to give your camera enough time to clear the image buffer before the next frame is taken.

Avoid dropped frames

Think of your camera’s buffer like a pipe connecting the newly recorded image and you camera’s memory card. It takes a little bit of time (depending on your image resolution) for the information to be processed and flow from one place to the other. If you try to send images too quickly some may get lost (your camera will skip a frame). Bad news. I’ll be explaining the concept of camera buffer “dropped frames” in greater detail in a separate post, but for now make sure your camera’s “read/write” light is off before the next frame is taken.

Bringing it all together:

Frame rate: Time-lapse compilations are commonly rendered at 24 or 30 (fps) frames (photos) per second. While there are other uses for other rates, this example will include a 30 fps compilation.

Interval Example: Fast clouds and a compilation length goal

It’s an awesome sky and fast moving clouds are being painted a warm orange from the evening sun. You have decided that you would like to create a 10 second cloud time-lapse compilation with an extra 2 seconds to fade in and out. Here’s what you calculated:

You want 12 seconds of compiled cloud footage to be shown at 30 frames per second.

This will require [ 12 x 30 = 360 ] 360 frames to captured.

You can see that the clouds are moving moderately fast and you want a nice smooth video. You decide to shoot at a 2 second interval.

At a 2 second interval and with the goal of 360 frames, you need to snap images for [ 2 x 360 = 720 ] 720 seconds or [ 720 / 60 = 12 ] 12 minutes (not including exposure time but that is minimal).

“Outstanding!” You think to yourself as you grab your copy of Atlas Shrugged and begin to setup for the shot. You can either program your intervalometer to shoot 360 frames at a 2 second interval, or you can set it to infinite frames and just watch the time. I usually do the latter (if I don’t need to save the card space for something else) incase something interesting comes into view I can just let it roll.

It’s worth mentioning…

If you are shooting a changing thing for the first time and aren’t really sure what interval to use, it is usually best to use one that is faster than you need rather than slower. You can always speed up too many frames in post but you can’t ever go back and capture those missing too slow intervals.

Return to The Massive Time-lapse Photography Tutorial:

[includepost id=”177″][/includepost]

Very helpful tutorial, especially with the table provided as reference.

Thanks for the great information! I’m currently doing a time-lapse of some Teasel seedlings. I’m recording with a webcam at 1 image every 5 minutes, and my film is going to be 15 fps. It’s looking good so far, so I’d say that your estimation of 90-120 seconds is good for playback at 30fps.

Great tips! Question, I know you said for situations where the light changes, like a sunset, you use aperture priority. Have you experienced with setting your ISO to auto? would that do essentially the same thing?

Thanks again!

[…] https://www.learntimelapse.com/time-lapse-photography-how-to-guide/how-to-select-a-time-lapse-interva… […]

These are excellent guidelines. To calculate the precise interval necessary to achieve a certain video length, I recommend this web app: http://www.packafoma.com/blog/2014/01/22/time-lapse-photography-interval-calculator/

[…] Kalau mau belajar lebih jauh cara membuat time-lapse, silakan ngesot ke di http://www.enriquepacheco.com/10-tips-for-shooting-time-lapse atau ke https://www.learntimelapse.com/time-lapse-photography-how-to-guide/how-to-select-a-time-lapse-interva… […]

Do you know if there is a calculator out there in which you plug in the length of the TLC video you are trying to create. We have a 2 month construction project, which we are trying to slim down to a 3 minute video. We have the Brinno TLC200 Pro, so it compiles all the photos into a video automatically. Any suggestions would be much appreciated.

Thanks,

If you make a 30 frame per second video that is 3 minutes long that gives you 5400 exposures. 5400 exposures spanned over two months gives you:

60 minutes * 24 hours = 1,440 minutes per day

1440 minutes * 60 days = 86,400 minutes in two months

86,400 / 5,400 = 16

You need to take a photo every 16 minutes to make a three minute long 30fps video that archives a 60 day event.

If you make a 30 frame per second video that is 3 minutes long that gives you 5400 exposures. 5400 exposures spanned over two months gives you:

60 minutes * 24 hours = 1,440 minutes per day

1440 minutes * 60 days = 86,400 minutes in two months

86,400 / 5,400 = 16

You need to take a photo every 16 minutes to make a three minute long 30fps video that archives a 60 day event.

Thank you very much. I have been searching for just this type of tutorial. You have addressed a ton of mistakes I’ve made so far.

[…] What will your time lapse interval be? Figuring out your time lapse interval can be complicated, and I'm a pretty simple guy, so read the linked article if you're the detail […]

Extremely helpful. Thank you so much. At least the basics have become clear.

[…] bem mais genérica sobre que intervalo usar em qual situação pode ser encontrada no site https://www.learntimelapse.com/ a […]